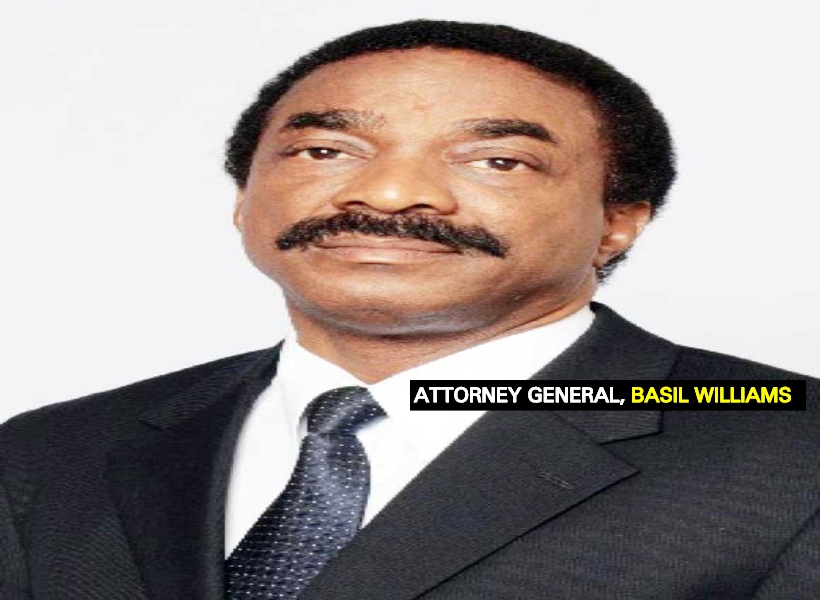

In his submissions on Consequential Orders, Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs Basil Williams told the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) that it cannot set a date for the holding of elections in Guyana. Williams said that the regional court has no jurisdiction to set a date or dissolve Parliament.

Williams submitted that setting a date for elections is a “quintessentially political question”—one of the most powerful tools held by a President or Prime Minister in most constitutional democracies, without fixed dates for elections.

According to the Attorney General, “Before setting a date for elections this Court (CCJ) must ask and answer the following question: What is the best date for general and regional elections to be held in Guyana? Frankly, that question and the answer to it are political in nature and within the exclusive right and privilege of the President of Guyana.”

Against this backdrop, Williams asserts that the courts of Guyana do not answer political questions, and urged the CCJ to remain above politics.

“It falls exclusively to the President to decide when to dissolve Parliament. It is noteworthy that Article 106 does not provide for the dissolution of the National Assembly by operation of law if a government is defeated on a motion of confidence. It follows that notwithstanding such a defeat, the power of dissolution remains constitutionally vested with the President. There is no evidence before this Court that proves or suggests that the President will fail to discharge his constitutional duty. Consistent with the settled practice of this Court, it is to be presumed that the President will comply with the law,” Williams put forward to the CCJ.

Williams in his submissions said that the Parliamentary Opposition and the other appellants in the No-Confidence Motion appeals are seeking coercive orders which are contrary to the basic legal principles for granting orders of Mandamus. The Attorney General is of the firm belief that there is no basis for coercive orders.

Mandamus is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do, and which is in the nature of public duty, and in certain cases one of a statutory duty.

Williams added, “Courts have been very hesitant to issue orders of mandamus, and have exercised such jurisdiction only where a litigant has established that a public authority has breached fundamental rights or failed to comply with a duty.”

He said that while the motion was passed on December 18, 2018, it was the subject to judicial scrutiny and it was not until June 18, 2019, that the CCJ affirmed that the motion was properly carried and that Article 106 of the Constitution was applicable.

“The President’s duties flowing from this Court’s decision with respect to the need for an election under Article 106 have therefore just recently been finally clarified. There is no evidence that the President has failed to comply with his duties. Consequently, there is no basis to order that the President act on his constitutional duty to set a date for elections or to dissolve Parliament.”

In this regard, Williams raises the questions of whether the courts of Guyana could make coercive orders against government in light of the fundamental constitutional principles including separation of powers—matters on which there has simply not been full argument before the CCJ.