Dear Editor,

My attention was drawn to a letter in today’s edition of Kaieteur News (June 6th, 2023), with the caption “we need answers”, by Rajendra Bissessar. I am obligated to respond since the author referenced one of my articles in the media. The author posed some questions where he is seeking some answers in relation to the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) that governs the Stabroek Block. I will therefore attempt to provide some answers.

Question (s)

“… Based on some figure, I think 60 USD a barrel of crude, “Cost Oil” would be 75%…I am asking if, considering that crude is being sold at over US$80, “cost oil” should be a lower % If not is EXXON getting a wind fall. Could someone or the government guide us as to what it means when the contract says shall be limited to 75% in any month? Am I to understand that 75% is a cap and so it cannot be more but could be less than 75% and given the high price of oil, “cost oil” should be less than 75%? From where I stand if no one, especially the government, tells me I am wrong and why, then this is daylight robbery and our government has no objections…if “cost oil” in any month is more than seventy Percent then the shortfall is recoverable in the succeeding months. So, if 75% does not reach “cost oil” they can recover the difference in subsequent months… if “cost oil” is less than 75% then they should take less than 75%”.

Answer (s)

The seventy-five percent (75%) is not the operating and production cost. It is the cost recovery ceiling inclusive of the total operating and production cost, which is lower than 75% according to the 2021 and 2022 financial statements. In 2021, for example, the operating costs represented 42% of total revenue and in 2022, the operating costs represented 26% of total revenue. Essentially, the purpose of the cost recovery ceiling serves two purposes: (1) to facilitate the recovery of the initial invested capital for the projects―that is, exploration and development costs quickly, and (2) at the same time, allow for the Government and the Contractor to cash in on the profit oil at the very outset.

Noteworthily as well, as evidenced in the cumulative statement of cash flow, once the costs are recovered, it is reinvested to develop future projects and fund the ongoing exploration activities.

So effectively, when prices are higher, this simply translates into a faster recovery of invested capital. In addition, as I have explained in a previous article in which I conducted a thorough financial statement analysis of EEPGL, Hess and CNOOC, I argued that the lack of ring fencing is typically applied to oil and gas fiscal regimes that is comprised of income taxes as part of the fiscal framework. In the case of Guyana, the Stabroek block PSA does not have an income tax component, per se, save an except for a nominal corporate tax.

Thus, the ring-fencing provision for this reason is not necessarily applicable because its purpose is usually to determine the taxable income in a given fiscal year. In hindsight, there is another important dimension that stakeholders should consider wherein the lack of ring fencing is an incentive favorable to Guyana. With the imposition of ring fencing, the cost of capital would have been higher than the current cost of capital and it would have restricted the current fast-paced development of future projects. As such, the lack of ring fencing is enabling future projects to be financed from the cash flows generated from Guyana’s operations, which is cheaper, versus sourcing capital from shareholders’ equity and higher levels of debt financing which would be more expensive.

More importantly to note is that the Stabroek Block’s PSA is not a perpetual contract. The PSA has a finite lifespan which means that at some point in the future it will expire. At the point of expiration, it is unlikely that all of the reserves will be extracted which means that following expiration, two things can happen. The first is that the new PSA with the new and improved fiscal terms will apply. And secondly, towards the end of the PSA, when all of the invested capital is recovered, the profit share in percentage terms is most likely to increase to about 60-70%, up from 25% during the cost recovery period.

With this in mind, the notion that the oil companies will benefit from a windfall if the operating cost is actually lower than 75% is not true. But of course, higher oil prices means higher profit, and since it is a 50-50 split, the government will also benefit from higher profit and royalty on account of higher prices.

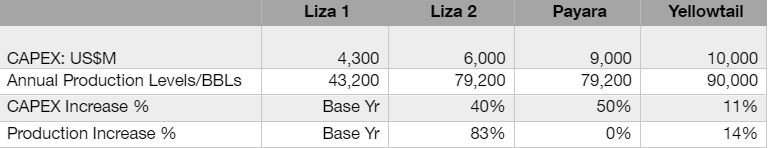

The author further questioned what could account for the “steep” rise in development costs for the other approved projects, namely, Liza 2, Payara and Yellowtail, relative to Liza 1. As shown in the above table, the capital expenditure (CAPEX) for Liza 2 increased by 40% relative to Liza 1, but its production capacity increased by 83% relative to Liza 1. The CAPEX for Payara increased by 50% relative to Liza 2 with the same production capacity. Conversely, in the case of Yellowtail, the CAPEX increased by 11% relative to Payara, and the production capacity increased by 14%.

There are several factors that can explain the cost variance for each project. The increase is not necessarily steep because each one of the FPSO is larger than the others and/or are all designed differently based on the characteristics of the wells within their respective fields. Moreover, each new FPSO are built with different features and newer technologies. In this regard, the construction of FPSOs requires building and integrating various components and structures. Certain selection and designing factors are considered for the development of FPSO in the oil and gas industry, including production capacity, hydrocarbon reserves, number of wells, water depth, and existing infrastructure constraining the building and operational flexibility. These factors impact the cost.

Another factor that impact the cost is inflation―such that globally, the construction and building cost for FPSOs increased significantly owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

So while the Payara project has the same production level as Liza 2, and the same amount of proven reserve, the number of wells and water depth, etc., are not the same. In fact, an examination of the project description for Liza 2 and Payara confirmed that Liza 2 is comprised of a total of six drill centers; 30 wells, including 15 oil producing wells, nine water injection wells and six gas injection wells. Payara, on the other hand, is comprised of ten drill centers; 41 wells are planned, including 20 production wells, 21 water and gas injection wells.

Altogether, these are the main factors that contribute to cost variance for the different projects.

Editor, I do hope the answers provided herein which is verifiable from publicly available sources are suffice.

Yours sincerely,

Joel Bhagwandin

Public Policy and Financial Analyst